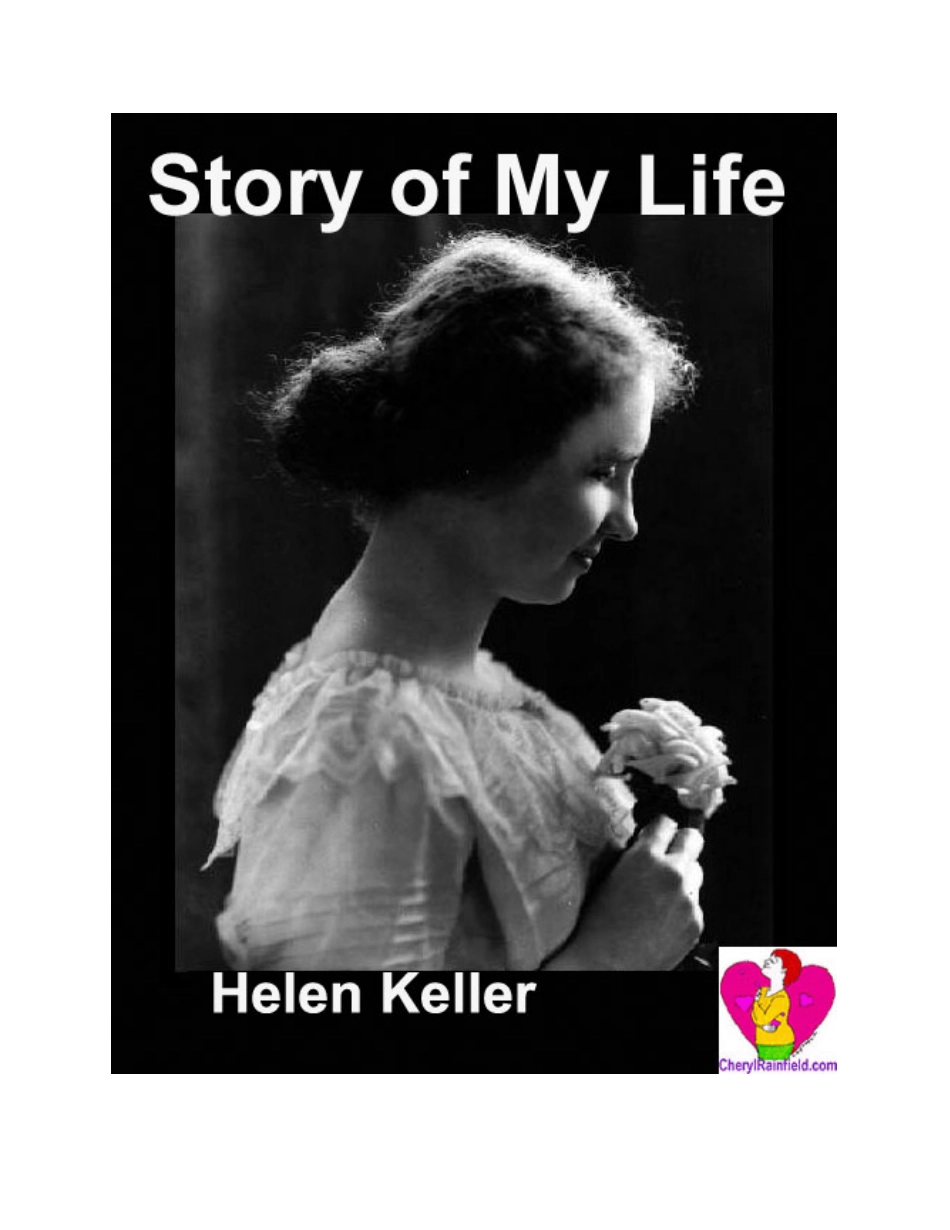

StoryofMyLifebyHelenKellerThisebookwasproducedbyC.Rainfield.Thisebookandmoreavailableathttp://www.CherylRainfield.comThisebookwaspreparedusingetextproducedbyProjectGutenberg,fromtheoriginaletextkelle10.txt.Thisebookversioncopyright©2003C.RainfieldAllRightsReserved1PartI.TheStoryofMyLifeChapterIItiswithakindoffearthatIbegintowritethehistoryofmylife.Ihave,asitwere,asuperstitioushesitationinliftingtheveilthatclingsaboutmychildhoodlikeagoldenmist.Thetaskofwritinganautobiographyisadifficultone.WhenItrytoclassifymyearliestimpressions,Ifindthatfactandfancylookalikeacrosstheyearsthatlinkthepastwiththepresent.Thewomanpaintsthechild'sexperiencesinherownfantasy.Afewimpressionsstandoutvividlyfromthefirstyearsofmylife;but"theshadowsoftheprison-houseareontherest."Besides,manyofthejoysandsorrowsofchildhoodhavelosttheirpoignancy;andmanyincidentsofvitalimportanceinmyearlyeducationhavebeenforgottenintheexcitementofgreatdiscoveries.Inorder,therefore,nottobetediousIshalltrytopresentinaseriesofsketchesonlytheepisodesthatseemtometobethemostinterestingandimportant.IwasbornonJune27,1880,inTuscumbia,alittletownofnorthernAlabama.Thefamilyonmyfather'ssideisdescendedfromCasparKeller,anativeofSwitzerland,whosettledinMaryland.OneofmySwissancestorswasthefirstteacherofthedeafinZurichandwroteabookonthesubjectoftheireducation--ratherasingularcoincidence;thoughitistruethatthereisnokingwhohasnothadaslaveamonghisancestors,andnoslavewhohasnothadakingamonghis.Mygrandfather,CasparKeller'sson,"entered"largetractsoflandinAlabamaandfinallysettledthere.IhavebeentoldthatonceayearhewentfromTuscumbiatoPhiladelphiaonhorsebacktopurchasesuppliesfortheplantation,andmyaunthasinherpossessionmanyoftheletterstohisfamily,whichgivecharmingandvividaccountsofthesetrips.MyGrandmotherKellerwasadaughterofoneofLafayette'saides,AlexanderMoore,andgranddaughterofAlexanderSpotswood,anearlyColonialGovernorofVirginia.ShewasalsosecondcousintoRobertE.Lee.Myfather,ArthurH.Keller,wasacaptainintheConfederateArmy,andmymother,KateAdams,...