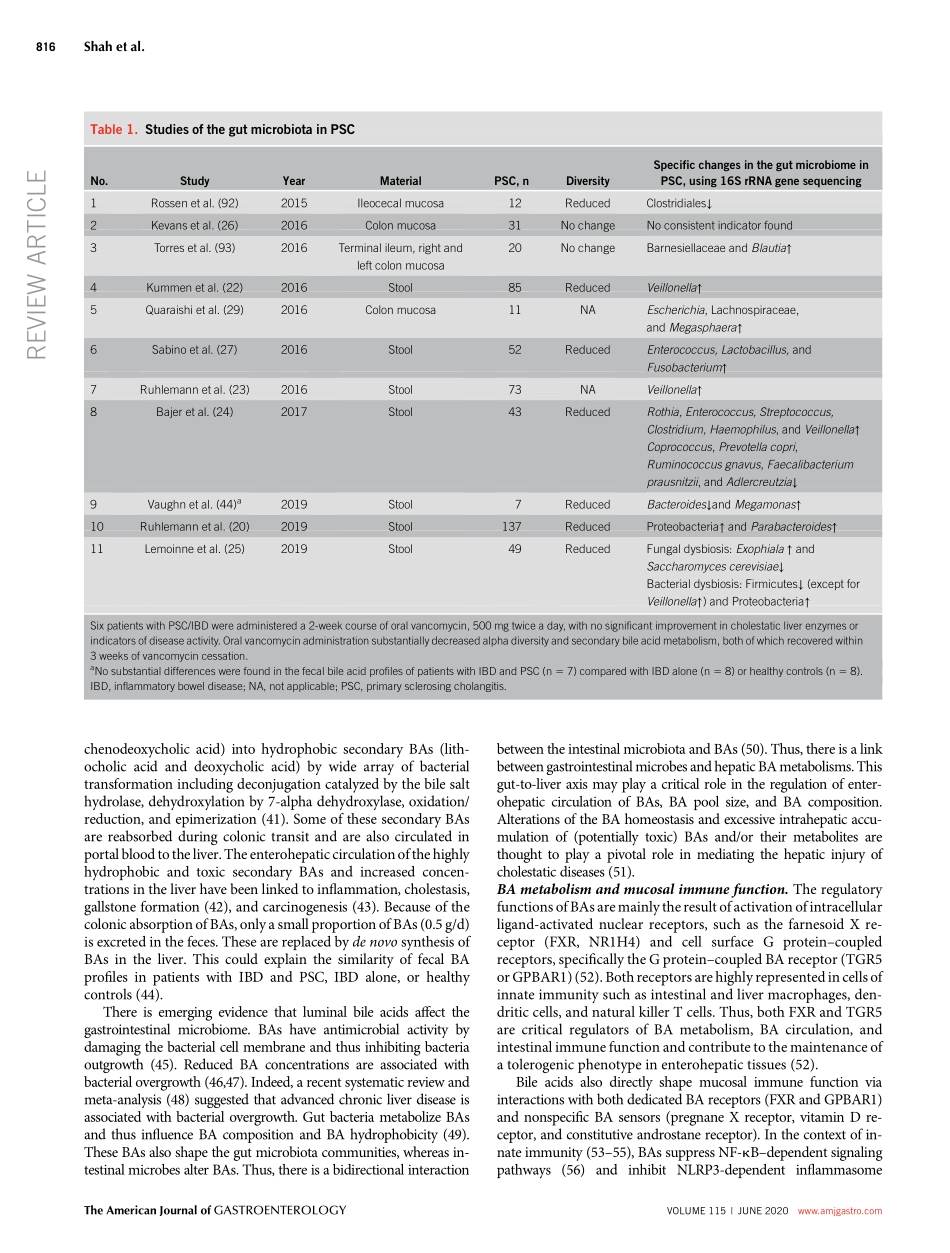

TargetingtheGutMicrobiomeasaTreatmentforPrimarySclerosingCholangitis:AConceptionalFrameworkAyeshaShah,MBBS,FRACP1,2,3,GraemeA.Macdonald,MBBS,FRACP,PhD,FAASLD1,2,3,MarkMorrison,PhD1,2,3,4andGeraldHoltmann,MD,PhD,MBA,FRACP,FRCP,FAHMS1,2,3Primarysclerosingcholangitis(PSC)isarare,immune-mediated,chroniccholestaticliverdiseaseassociatedwithauniquephenotypeofinflammatoryboweldiseasethatfrequentlymanifestsaspancolitiswithright-sidedpredominance.Availabledatasuggestabidirectionalinterplayofthegut-liveraxiswithcriticalrolesforthegastrointestinalmicrobiomeandcirculatingbileacids(BAs)inthepathophysiologyofPSC.BAsshapethegutmicrobiome,whereasgutmicrobeshavethepotentialtoalterBAs,andthereareemergingdatathatalterationsofBAsandthemicrobiomearenotsimplyaconsequencebutthecauseofPSC.ClusteringofPSCinfamiliesmaysuggestthatPSCoccursingeneticallysusceptibleindividuals.Afterexposuretoanenvironmentaltrigger(e.g.,microbialbyproductsorBAs),anaberrantorexaggeratedcholangiocyte-inducedimmunecascadeoccurs,ultimatelyleadingtobileductdamageandprogressivefibrosis.Thepathophysiologycanbeconceptualizedasatriadof(1)gutdysbiosis,(2)alteredBAmetabolism,and(3)immune-mediatedbiliaryinjury.Immuneactivationseemstobecentraltothediseaseprocess,butimmunosuppressiondoesnotimproveclinicaloutcomesoralterthenaturalhistoryofPSC.Currently,orthopticlivertransplantationistheonlyestablishedlife-savingtreatment,whereasantimicrobialtherapyorfecaltransplantationisanemergingtherapeuticoptionforPSC.Thebeneficialeffectsofthesemicrobiome-basedtherapiesarelikelymediatedbyashiftofthegutmicrobiomewithfavorableeffectsonBAmetabolism.Inthefuture,personalizedapproacheswillallowtobettertargettheinterdependencebetweenmicrobiome,immunefunction,andBAmetabolismandpotentiallycurepatientswithPSC.AmJGastroenterol2020;115:814–822.https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000000604INTRODUCTIONDefinitionsandclinicalpresentationPrimarysclerosingcholangitis(PSC)isanuncommonchroniccholestaticliverdiseasecharacterizedbyinflammationandfi-brosisofin...